At its essence, design is creative problem solving that can be applied to solve an infinite number of problems. To prepare our students for the future of design, design professors must embrace teaching young designers to be adaptable. Graphic designers are often called upon to be image-makers, illustrators, typographers, communicators, and sometimes even developers. While these conventional skills are important, it is also valuable to be researchers, content creators, inventors, leaders, business owners, entrepreneurs, and visionaries. As the industry evolves, so must our approach to teaching.

Historically, we’ve trained designers to be visual communicators, but those in the profession are called on and capable of doing much more in today's world. The connecting factor design professors can teach is that all designers are creative problem solvers who can impact the world. Richard van der Laken, the founder of What Design Can Do, said it best:

“Every self-respecting designer should do something. Come up with new ideas, dust down old ideas and place them in a new context. Silence the cynics. Let the politicians know that wheeling and dealing achieves little. Prove that actions speak louder than words. Demonstrate the power of design. Designers can do more than make things pretty. Design is more than perfume, aesthetics, and trends.”

My teaching philosophy and methods are pliable, balancing teaching creative problem solving with guiding students through the essential technologies needed to make ideas come to life. It is easy to get wrapped up in the nuances of teaching technical skills and to forget how our students will apply what they have learned when they graduate. Not all students have the same goals, and many are unaware of all of the directions they can explore in their careers and creative lives. Students can have tunnel vision and focus most of their energy on being the best visual designers, which can cause them to miss seeing the bigger picture—the value they bring as creative problem solvers. My goal is to empower students to use their design education to find their unique paths.

One way I accomplish this is by bringing collaborative design practices to my classroom. While we spend a lot of time in the design classroom talking as a group, traditionally most assignments in design education are individual-based. In contrast, when students enter the workforce, they are often joining a team where group work is the norm. To help prepare students for this transition I have been focused on incorporating more group work into my curriculum. Whether it is an assignment that begins with group research, a quick partner exercise, or a semester-long team project, I work to provide my students with opportunities reflecting a design practice in the 21st-century—including research, communication, collaboration, leadership, flexibility, and time management. Learning to work together, to use your strengths, and recognize the strengths in others is a skill that will be used throughout professional life. Group work presents new challenges to learn from and can create superior solutions when approached with an open mind.

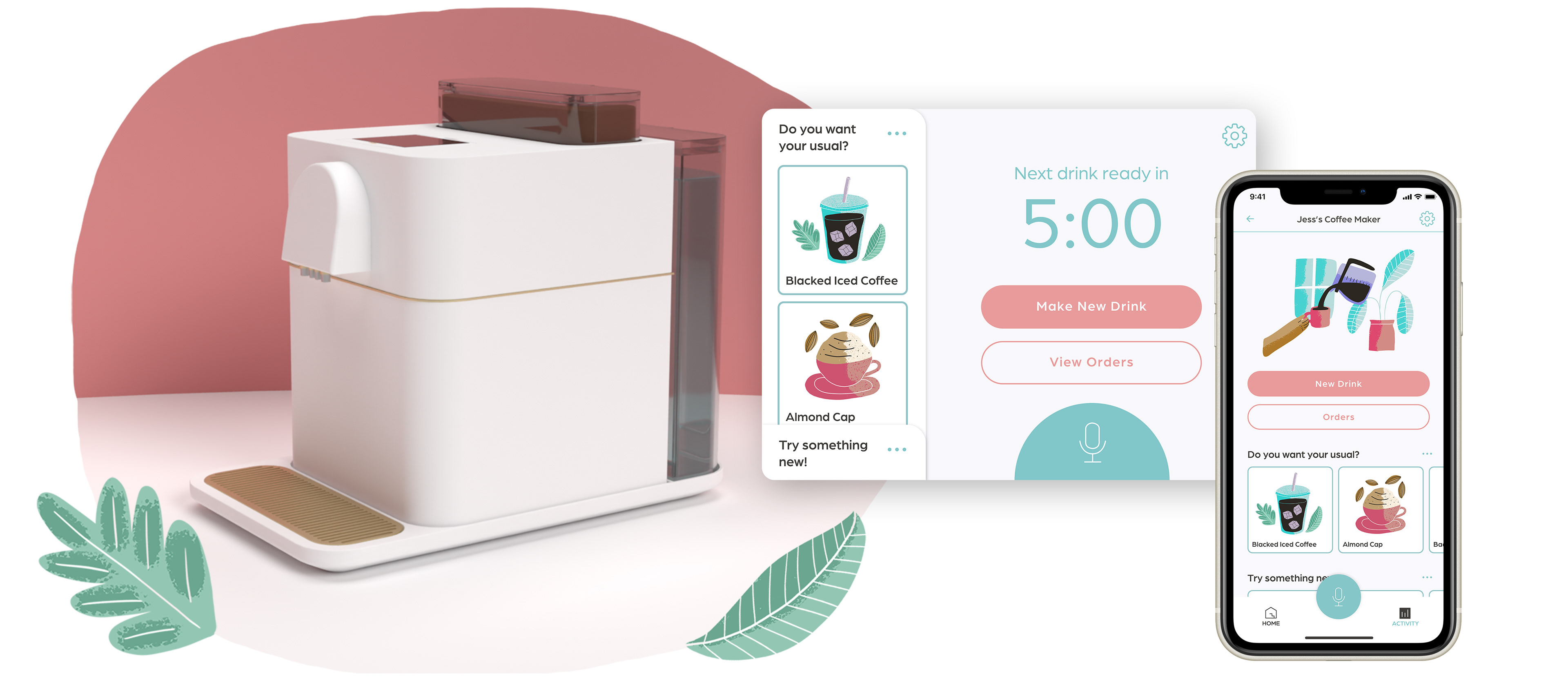

In the past few years, I have focused significant time researching User Experience Design (UX Design) and this research has become significant in my teaching. I am interested in this field because it is at the intersection of strong visual design and the science of how a specific audience uses a designed product. UX Design embraces typography and communication but also pushes the designer to be a researcher so they can create a solution that works for its user. While not all of our students will use research skills to become UX designers, they can benefit from practicing design research. I encourage my students to become subject matter experts for any project they are constructing. I walk them through the design research process, encouraging them to employ a human-centered approach. Once they understand all facets of a problem, they can start to craft a solution. I expose students to various research methodologies, often sharing my own approach through projects I currently am working on. I want my students to gain foundational research skills, but have the flexibility to adjust their process to adapt to any given project.

Making the jump from research to design can be challenging. It is difficult to assemble research into a system that allows the designer to use what they have learned to explore different approaches to solve a problem. I teach students how to build a system to organize their research so they will set themselves up for success. When they move to the design phase, they quickly learn that iteration is part of this process and the earlier they fail the more opportunity they have for growth. Design is a circular process with room for continual improvement. Design research is not the first phase to complete before moving on to design; it is a key element to be revisited throughout the lifespan of a project. Input from peers, advisors, and the end-user can confirm a direction, or provide feedback to take a project on a new path. Ultimately it is our job as designers to communicate a particular message, and we cannot do this in isolation without feedback. I encourage my students to seek feedback, to test their design with the intended audience to ensure they are communicating effectively. We must be open to critique and willing to accept that we can always improve an idea, a visual approach, or a solution.

I have also worked to keep up with design technology as it evolves. Most recently I have taken up 3D design, learning new digital tools and using them in the classroom. This work has paid off as I was asked to co-host a session at Adobe Max in 2020. Adobe Max is one of the largest creative conferences around. In 2020, over three days, Adobe Max attracted about 10 million views and had 600,000 attendees. The session I co-hosted, “Adobe Dimension and Stock: Creating High-Quality 3D Content to Transform Your Curriculum” had 1713 attendees at the live broadcast, and over 2,000 watching since. The session received a score of 4.84 out of 5, with a speaker score of 4.9 out of 5.

The teaching of the newest design tools and technologies often feels like an unattainable task. New software and software updates are being released at a speed that feels impossible to keep up with. In order to address this, I recently collaborated with a colleague to rethink our department's approach to teaching foundational technical skills. The curriculum within which we implemented these changes is a required course at the sophomore level; our student's first technical class in our major. The class now focuses on teaching our students how to learn technology. We accomplish this by using UDL (universal design for learning) techniques like providing the students with a variety of methods to learn a skill. For example, when teaching how to complete a task in the software we may provide LinkedIn Learning demos, written demos, TikTok tutorials, and also demonstrate the task in class ourselves. The students also have weekly learning journal entries required where they reflect upon their learnings from the past week. Finally, the student's final project is to create their own tutorial for a skill they learned during the semester.

In order to ensure my students are comfortable accepting feedback, I work to create a classroom atmosphere that fosters each student’s ideas. Part of being a professional visual communicator is being an effective verbal communicator; students can improve their verbal communication skills through both group brainstorming sessions and group critiques. Knowing some students are better suited for smaller group conversations, I try to vary how critiques are delivered in my classroom. I facilitate some full-class discussions and some smaller, intimate group critiques. Completing the Provost’s Teaching Academy at Temple University grew my interest in experimenting with new approaches to the traditional critique and I plan to create resources for other faculty to help students develop the tools needed for successful participation in group critiques. One concept I’d like to explore is taking the concept of “conversation moves” and adapting it for classroom design critiques.

In conclusion, I work to ensure my students view their design degree as the strong foundation needed to begin their careers. Not simply a means to an end, but a fundamental platform for their unique path to success. I encourage my students to tackle problems they may initially think are outside their realm of knowledge. Often my students walk away from our time together not only having acquired marketable skills but also with the courage to take on challenges they may have initially felt inadequate to conquer. This is the heart of my teaching philosophy. I love design. I love typography. I love illustration. I love creative problem solving. But most of all, I love teaching designers that they can apply their creative problem-solving skills in an infinite number of ways including becoming leaders and entrepreneurs. While they should respect the industry and all they can learn working in a great studio, they also have the opportunity to carve their own path. Hopefully, I help them see that if they want to they can do more than simply “make things pretty.”